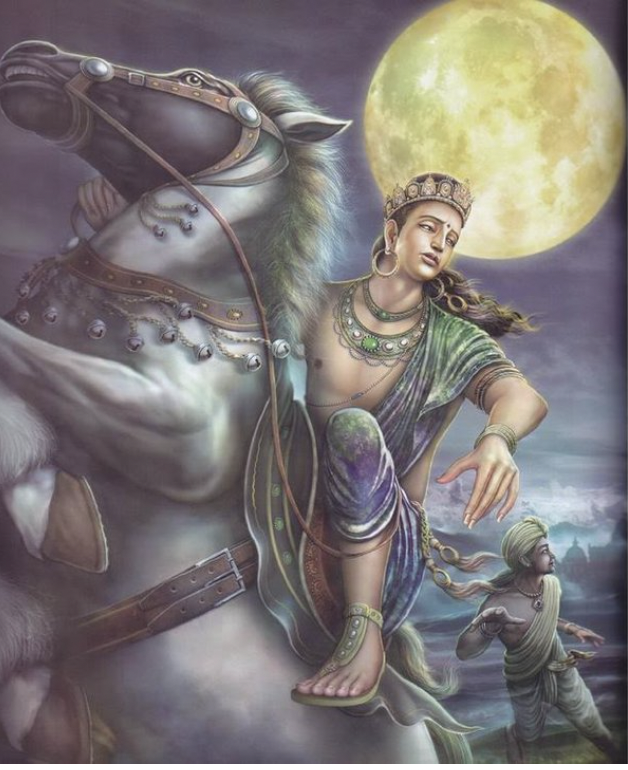

On the first night of our sesshin (residential retreat) celebrating the Buddhist holiday of Rohatsu, we read a pretty standard, simplified recounting of the story. It starts with Siddartha Gautama riding away from his family and palace and ends with his transformation into Shakaymuni Buddha. The plot is pretty familiar, really.

It is sometimes said that there are seven (or sometimes four or six) basic plotlines–plotlines that are used over and over because we tend to find them particularly satisfying.

In “the quest” plotline, the protagonist must obtain some object or get to some particular place, while, largely by their own strenuous efforts and cleverness, conquering many obstacles along the way. The Odyssey is a classic example; The Lord of the Rings, more recent. We hear that Siddartha Gautama went on a quest for Enlightenment. He had to leave home to do so, and nearly died from ascetic practices along the way.

Another classic plotline is called “overcoming the monster.” Starting with ancient stories like Beowulf, this involves a hero who must vanquish some sort of evil power. Think early Star Wars, or James Bond movies. Siddhartha, we are told, went head-to-head with Mara while sitting under the Bodhi tree. In the end he decisively triumphed.

The story ends when the thing sought for on the quest is found or the monster is overcome. And the hero, the story states or implies, lives “happily ever after.”

Both the quest and monster plot lines are included in what Joseph Campbell has called the “monomyth” which he claims underlying all mythological stories. He summarizes it like this:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

Bingo. Our classic Rohatsu story is just such a hero narrative. Siddhartha, we hear, achieved something we call “Enlightenment” and became a Buddha. Then, tradition says, he passed it on (“transmitted” it) to his disciples.

But need it be a hero narrative? Should it be? Is this what Buddha, Enlightenment, and Zen, are really about?

I don’t think so. Something seems to have actually happened to a historical Shakyamuni, as far as historians can tell. But what this was, we only know about because of somewhat inconsistent stories, carried along through oral tradition, within male-dominated societies, for hundreds of years.

We can get some idea of what has gotten left out or suppressed by our plot-line preference two ways. First, we can examine how it contrasts to a different sort of classic plot line. Second, we can note the difference between stories and actual life.

A Contrasting Plotline

The classic protagonist in hero stories was always a male; females only had supporting roles. When, once in a while, there has been a female protagonist, a story line has been, instead, “the damsel in distress.” Think Sleeping Beauty or Cinderella. Many hero plot lines are also of this nature, when looked at from the perspective of a female character. A girl or woman is lost, captured, or under a spell, and is rescued by an outside force–a Prince Charming or a Luke Skywalker. (This plot line, by the way, has not been considered culturally central enough to make most shortlists.)

Note three differences between the “hero stories” and the “damsel stories”:

- While the male hero is active, going forth on quests and battles; the damsel is passive, staying in place. If not sound asleep, she is likely tied down by care of her (step-)family–or a houseful of people with names like Sleepy and Grumpy.

- The hero is saved by his own efforts; the damsel by the beneficent action of someone or something else.

- The hero acts alone; the damsel is seen primarily in relation to others, as a daughter (princess) or a love interest. She may also be portrayed as more embedded in nature, for example living in a forest or associated with nourishment.

Yet our Zen practice is profoundly non-dualistic. I believe that these gender dualisms are among those most profoundly challenged. So how do these contrasting storylines relate to our practice?

1. Venturing forth and staying in place

We do set out, in our Zen practice. We are enjoined to “put our foot on the path” or “take up the Way.” These are both travel metaphors. We do need to move out of our usual comfort zone. Our self-centeredness is habitual; Zen challenges that. If we’ve ever tried koan work or reading Eihei Dogen, it becomes especially obvious that we “aren’t in Kansas anymore.”

And yet this Way leads us right back here. Do we really have to go anywhere? Our central Zen practice, after all, is “just sitting.” When did Shakyamuni’s breakthrough come? When he sat. When we really sit we stop trying to get somewhere, or get something. As Dogen reminds us, we do not practice to get to enlightenment; practice is enlightenment.

Here is a lovely poem that illustrates this point:

The Lay[person]’s Lament

by Judith Collin

Shame on you Shakyamuni for setting

the precedent

of leaving home.

Did you think it was not there –

in your wife's lovely face

or your baby's laughter?

Did you think you had to go elsewhere

to find it?

Tsk, tsk.

I am here to show you

dear sir

that you needn't step

even one sixteenth of an inch away – stay

here – elbows dripping with soapy water

stay here – spit up all over your chest

stay here – steam rising in lazy curls from

cream of wheat

Poor Shakyamuni – sitting under the Bo tree

miles away from home

Venus shone all the while

We go forth to enter life as it is right here and now.

2. Own-power and other-power

It is true that we need to be diligent and determined in our practice. We can’t just wait around for things to happen to us. We are enjoined to practice “as if putting out a fire in our hair.” Only we can get our butts on our cushions. It’s up to us to locate (or form) a sangha. In this sense, we are our own heroes, not just passive recipients.

And yet everything we receive, we receive by grace. Our lives, our food…and our insights. Siddhartha’s strenuous efforts to learn from yogis and to punish his body had failed to bring him to enlightenment. The turning point came when he recalled sitting under a tree as a boy, watching the plowing of a field, and without effort or will experiencing oneness the insects and the birds. Going to sit under the Bodhi tree, he recovered his childhood openness and receptivity. The 10,000 dharmas came forth to enlighten him.

We can’t earn enlightenment. We are rescued by grace.

3. Alone and in Community

As Reb Anderson has said, “nobody else can do [our practice] for us.” We each need to sit, alone and silent on our own cushion. We need to realize Buddha nature for ourselves. Nobody, not even the most revered teacher, can “bestow that boon” on us.

And…that was only half of the quote from Anderson. The other half is “We can’t do it by ourselves.” We rely on grace. And we also rely on other people. While hero stories tend to underplay help from–not to mention profound interdependence with–other beings, the Rohatsu story itself cannot completely avoid it. We are told that Siddhartha was saved from death when he received a bowl of rice and milk from a young woman named Sujata. If there had been no Sujata, there would have been no Shakyamuni Buddha. No Shakyamuni, and we’d all be doing something else instead of reading a Buddhist blog post. Shakyamuni Buddha also called on the entire earth to be his witness in his battle with Mara. He later went on to form a community. We take refuge in the sangha.

One has no separate self. How could one be a lone hero?

A story from 17th century China (found in The Hidden Lamp, abridged here) speaks to this beautifully.

Ziyong’s Earth

A monk said to Master Ziyong Chengru, “When you speak, the congregation assembles like clouds. In the end, who is the ‘great hero’ among women?”

She replied, “Each and every person has the sky over their head; each and every one has the earth under their feet…If I take up the challenge of speaking I must surely borrow the light and the dark, the form and the emptiness of the mountains and hills and the great earth, the call of the magpies and the cries of the crows.”

We play our part, and always in total interdependence.

Stories and Real Life

No matter what story line(s) we might use to describe our practice, there remain some important differences between stories and real life.

Stories are fictional. They tend to follow predictable tropes. They describe only a limited-duration part of the life of a person, nation, or family. They end with a satisfying resolution.

Life is real. Life is characterized by unpredictability. Our existence is marked by impermanence, including impermanence of anything we think we might have achieved or gained along the way. The only resolution to a story of a full life is its end in death.

When we try to reduce enlightenment (or “awakening,” “realization,” etc.) to something we can fit into a storyline, we tend to force on it a “happily ever after” ending. We treat enlightenment as a “thing” that one can “get” and hold onto. But permanent enlightenment is–literally–a myth. Enlightenment is our practice. It comes in glimpses. It’s always now. It is how we try to live.

And so, may I add, there are also no heroic fully and permanently enlightened Zen teachers, with disciples waiting to be rescued. That understanding stays firmly within the hero/damsel story that Zen explodes.

Following the example of Shakaymuni Buddha, we need to be willing to bravely venture beyond the familiar, be tenacious, and pay attention to our own inner compass. And we need to be satisfied with where we are, be receptive and open, and practice in community. Finally, we need to do all these things all our lives, not just for the time it takes to tell a story.

A recording of this, as given as a talk at the Greater Boston Zen Center 2022 Rohatsu sesshin, can be found in the Center’s podcast series.

Virtuous Master, thank you for today’s teaching. I learn a lot from reading your words. Season greetings! Tae-Hee

LikeLike

>You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table

and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait. Do not even wait, be quiet

still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be

unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.”

-Kafka

LikeLike

Thank you for these words (and for Judith Collin’s lovely poem). I’ve been reading your posts about teacher-student interactions, the pitfalls and needed boundaries as well as the useful bits, and they have been immensely helpful. Thanks for sharing how your sangha is structuring itself to help avoid some of the more problematic issues with teacher-student connections.

(As a side note, it would have been fabulous to receive a matriarch chart at my jukai ceremony.)

LikeLike