There is much to recommend Nancy Mujo Baker’s new book on the Zen Precepts. And there are some passages I am concerned about. In this, the second of two posts, I want to explain why I find a few passages that touch on abuse of students by teachers to be alarming.

Baker’s book is, of course, not specifically “about” abuses by teachers, but about the precepts more generally. Yet, to the extent that communications by Zen authorities add to the widespread ignorance and misunderstanding of issues surrounding teacher power in Zen sanghas, I feel I must speak out about them.

The first passage I feel I need to challenge is on p. 53 of of Opening to Oneness:

“What about sexual relations between teacher and student? Or between therapist and client? Or between two adulterers? Are these consensual? Here, perhaps what we need to look at–on both sides–is self-deception and motive, particularly unconscious motives.”(p. 53)

Uh…no. Sexual relations between a spiritual guide and student or between a therapist and client are non-consensual by definition, because of the power differential. They are considered unethical, and could be illegal, in every state in the U.S. (Many states impose criminal penalties on such relations; in all states, they are subject to challenge under civil law.) And the responsibility for making sure that appropriate boundaries in the relationship are maintained never rests on the student or client. That responsibility belongs entirely with the Zen teacher or therapist (and the board of directors or regulatory bodies that supervise them). This is not a matter of opinion, but of basic ethics and law.

Zen teachers and clergy, like therapists (and lawyers and physicians) are all in a “fiduciary” (duty of care) relationship with their students or clients. That is, someone has come to them asking for their help, and they have a professional duty to put the interests of that person first. Zen teachers hold a great deal of power whether they recognize it or not. Students look to them for, at the least, spiritual guidance, and often entrust them with sensitive personal information in the dokusan room. But there is more to it. Many if not most students arrive with at least some degree of naivety. It’s easy, when one feels oneself in need of help, to idealize the teacher, to think that they “have” something that “I need to get.” Encouraged by parts of our tradition, their sangha peers, and the teachers themselves, students may believe that deferring to their teachers’ (presumed) greater wisdom in all things is their only chance at enlightenment.

But it really doesn’t matter how naive a student is. It doesn’t even matter if their “unconscious motives” cause them to come on to their teacher sexually! It’s a teacher’s job to see that the relationship functions always and only in the student’s best interest. If the student really “needed” sex, they could have gone on an app or to a bar. If a student comes to a zendo and talks with a teacher, the seeking of spiritual guidance is assumed. An ethical Zen teacher should recognize that feelings of attraction, no matter how powerful, are simply feelings arising and not let them get in control. Seeking guidance from peers or a therapist, and perhaps taking a sabbatical from teaching, may help.

What if both the teacher and student feel that the relationship is “consensual”? It still doesn’t matter. The only way to tell if an authentic personal relationship could be possible is to see what happens after the teacher-student relationship is broken off. There can be no real consent until the student has had time to get free of the dynamics of power. For therapists, for example, a waiting time of two years is recommended. During that period (and not before), the (now) former student would be well advised to spend some time “look[ing] at…[their] motives.” It may turn out that they weren’t, in fact, attracted to the teacher as a person, but instead awed by their draping in teacher robes.

Any serious study of the dynamics of the teacher-student relationship (I recommend these resources) would show how different this relationship is from one “between two adulterers” where neither has more power than the other. Yet a lack of attention to teacher power also surfaces in two more entries in Baker’s book, one of which provides the title of this blog post.

In the chapter on “Non-Lying,” Baker points to,

“…a very important failure to tell the truth—namely, the failure to speak up. With all the talk recently about sexual and other forms of misconduct among dharma teachers, it’s surprising how little attention is paid to students failing to speak up.” (p. 62)

It is not the student’s responsibility to speak up: It is the teacher’s responsibility to not abuse their power. Someone has been abused, and now they are further labeled a “failure” and a precept breaker? This is not the Zen approach as I understand it.

Why might a student not speak up? The teacher may assert their power directly, for example by threatening to reveal secrets confidentially shared in dokusan if the student talks to anyone. But such a direct show of power is usually unnecessary. Given the history of Buddhist sanghas in the Western world, the student probably already understands the likely consequences. The teacher would likely deny or at least minimize the abuse. Who are people more likely to believe, their dear and revered Roshi, or some student they may never even have met? The student is more often than not labeled a liar, shamed, and ultimately driven from the sangha. Or the teacher might just be a good manipulator, framing the situation in such a way that the student doesn’t even realize they are being abused (until, perhaps, much much later). The student is told they have a “very special spirit,” the sex is called a “path to enlightenment,” and/or the teacher pleads that they would be heartbroken and have to leave Zen (or worse) if the student broke things off. Emotional and financial breaches of trust may be similarly sheltered from public scrutiny.

Lastly, in the chapter on “Non-Misusing Intoxicants” Baker writes,

“We all know the substance category–drugs, alcohol, food, sugar, caffeine, nicotine. But there are other less obvious categories. Daydreaming…So are blaming, analyzing, justifying, and storytelling. I need to tell my story; I need for you to know who I am…Obsessing…Tuning out…Being a victim.” (pp. 70-71)

Perhaps the issue here is more subtle than for the passages I examined earlier. It is true that it is possible for people to get overly attached to telling their personal story or identifying as a victim. But it is also true that those harmed by abuse of power by Zen teachers are, indeed, victims. Sometimes that word is avoided in favor of terms appropriate for describing conflict between people of equal power. That grossly mischaracterizes the problem. While one should hope that the person victimized will not attach permanently to victimhood, and will get the help they need to move on to being a survivor, simply “being” a victim is not a violation of the precepts.

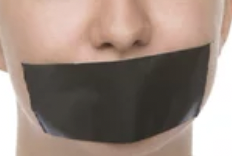

Storytelling, per se, is also not a violation of the precepts. One of the most healing things one can do for a victim of abuse, in fact, is simply listen to their story. They have been silenced, their voices squashed and demeaned. Telling them to quit talking about themselves and “get back to the Dharma” encourages spiritual bypassing at its worst.

One thing that is most definitely a violation of this precept is intoxication with power. This is a well-studied phenomenon in psychology, organizational behavior, and neuroscience. People who get used to having power often tend to become overconfident in the rightness of their views, reckless in their actions, and demonstrate little empathy for, or willingness to listen to, others. But power, unfortunately, is not anywhere in the list of intoxicants that Baker mentions. Nor is the issue of teacher power addressed anywhere else in the book.

Baker’s book will be helpful, in many ways, for students who want to learn how to live by the Zen ethical precepts. But I believe we–meaning the Zen sangha in its widest form–need to put much more effort into understanding how those entrusted with giving spiritual guidance can live by the precepts. We need to devote considerably more time to studying power, the problems associated with intoxication of power, and how our practices or other structures might sometimes encourage such intoxication. Maybe then the continuous cycle of sexual and financial scandals in so many of our communities could finally come to an end.