In the yin-yang diagram, both light and dark are necessary, and their relationship is dynamic. But in our habitual Western thought not only do we separate the two and think of them as fixed, we tend to associate light with superior and dark with inferior.

Europe, we say, was lost for centuries in “The Dark Ages,” characterized by ignorance and superstition. During “The Enlightenment Era” these were “vanquished by” the rise of reason and science. In old “Western” movies, the good guys wear white hats and the bad guys wear black hats. And we haven’t gotten past the way this works in our imaginations. In contemporary films and literature, for example, “magical negroes” often appear—supporting (never lead) characters who metaphorically represent earthiness and mystery.

What I’ve called “entity thinking” (see Nonduality Part I) is an inheritance from that European Enlightenment. And it was very useful, it was—at least for a time. Technologically, it was useful to move away from the medieval vision of the nature as fundamentally mysterious and uncontrollable, its processes understood only by God. “Laws of nature” became expressible in physics equations; parts were assembled in mechanical systems. Modern science and industry were born. In the political sphere, images of a God-given-order justifying the hierarchy of lords over serfs faded. Ideals of individualism and equality arose.

Recall that in “entity thinking” we consider the world to be composed of entities (that is, things or objects) that first exist in themselves, and then engage in action and relation to each other. Parts made of metal are assembled into machines. Individual citizens are imagined to agree to a “social contract.”

Three Types of Relationships

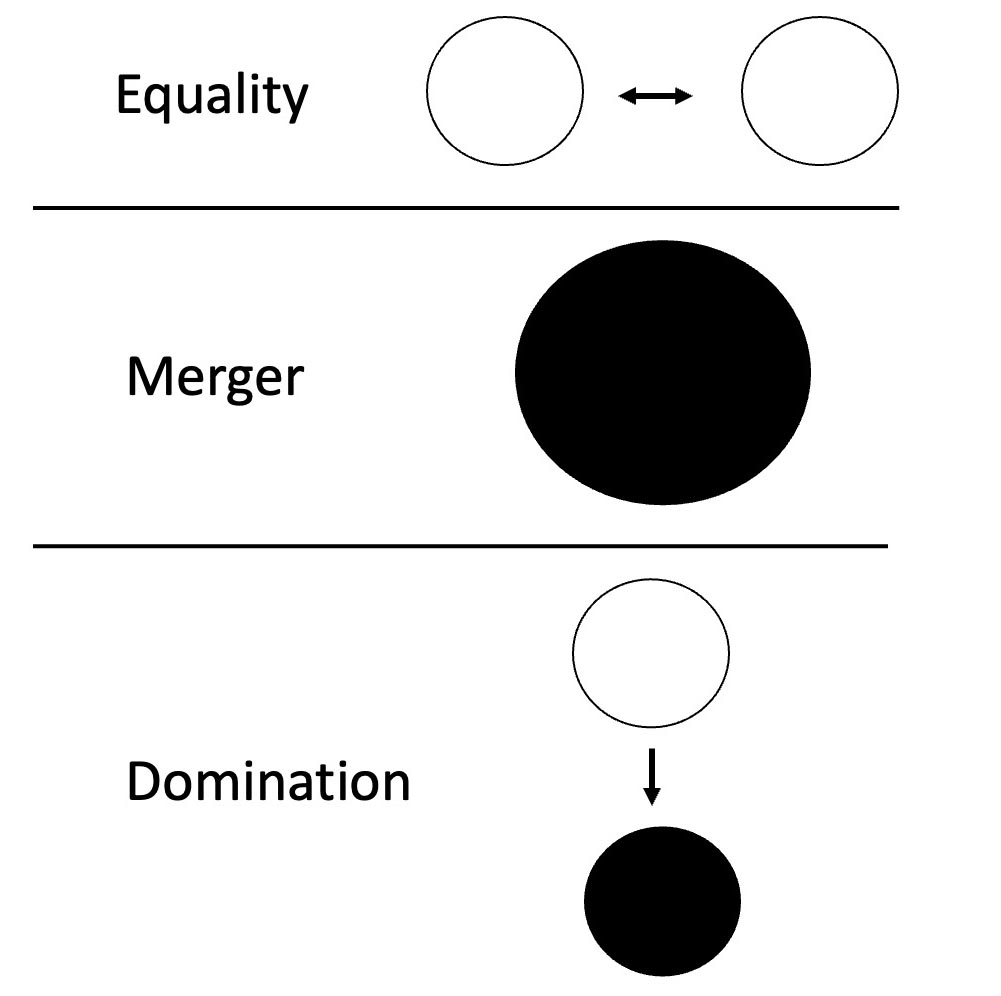

If this is the kind of thinking we are stuck in, we can only see very limited, non-overlapping possibilities for how we relate to each other.

The first is a static equality. You and I are each separate, autonomous actors, and meet at arm’s length with exactly equal power. This is the political ideal of a democratic citizenry, where, while people may sometimes disagree, neither can dominate. Economists’ central model of an idealized competitive market assumes that all actors have equal power. Socially, this may resonate with our relationship to our peers in friendship, and/or to a conflict with a co-worker than ends in a stand-off. To borrow the colors used in the yin-yang diagram to indicate activity and passivity, we are each a pure white (active) circle, meeting on a level playing field:

The second is a static merger. We really are one, and act as one. The image of merger may be inspiring. Politically, it is an image of perfect consensus or “solidarity.” Most religions make references to some kind of mystical perfect union. Socially, marriages and families are often idealized in this way. As humans, we seek out stronger bonds than just arms-length transactions or friendship. We also seek peace. Erasing distinctions and boundaries among ourselves, and submitting our will to that of the whole (passive, black) we together form a black circle:

But the idea of merger can be also be terrifying, if we put a high value on our individuality and distinctiveness. At a political level, merger may seem to imply a suppression of all dissent and diversity. Existentially, we may fear it as a drop into a sterile and characterless void. Under old English law, it was said that in marriage the two became one—and the one was the husband. The wife was erased.

Here is the root of the many-and-one confusion. We can be two, with no dependence on each other, as in the equality diagram. But that is rather lonely, and also could just lead to a protracted conflict. Or we can be “close” and at peace, as in the merger diagram. But then we lose our individual identity. Neither seems particularly satisfying.

And there is a third possibility: Domination. You are active and I am passive, so you dominate me. Or vice versa. The active party is the pure white circle, who together with a pure black, passive, circle, creates a static hierarchy:

Only one opinion here matters; there is only one active and powerful party, while the other passively accepts direction. One accepts the dictates of Id Duce, God, one’s husband, or one’s father.

Equality Wins Out

Our Anglo-American culture puts very high value on rationality and the individual. As a result, we have a tendency to think that only the first case (static equality) represents an ethical, non-oppressive idea of identity and of the uses of power. Merger tends to be dismissed as disrespectful of the individual or as mystical nonsense. Domination is seen as an oppressive throwback to those old “Dark Ages” of lords and serfs. Or so our options seem to be, when we are stuck in “entity” thinking.

When we think in these terms, and observe abuses of power in a situation of domination, the only fix we may be able to imagine is to get rid of hierarchy and meet as equals.

And now we get to the nub of why I’m writing all this now: In my sangha, we witnessed senior teachers acting arrogantly and causing great harm. Whether teachers acknowledge it or not, they have power vis a vis students. The tradition of teachers’ “transmission of the Dharma” (authorization to teach) to a next generation of teachers creates a hierarchical divide between the “transmitted” and “non-transmitted.” It may seem that the only answer to abuses of power to get rid of the tradition of Zen transmission, and say we are all democratically equally teachers.

Or Does It?

If we come down out of our theoretical clouds, though, the fact that static equality is not always possible is glaringly obvious. I first became aware of this problem in my professional work as a feminist economist. Standard economics is centered around the image of the rational, autonomous actor acting in competitive markets—that is, an image of static equality. It also contains hidden images of cool, structural domination (e.g., bosses make decisions while workers presumably exchange their self-direction for pay) and merger (e.g., a household is represented as an “individual”).

Yet women have traditionally made significant parts of their economic contributions outside of markets, as well as in relationships in which they are charged with caring for vulnerable people. There are undeniable power differences between a mother and child: The child does not decide their own bedtime, or when to cross the street. There are undeniable power differences between a nurse and a sick person: The nurse controls the access to morphine. There are likewise power differences between a social worker and homeless person, and between a primary school teacher (who knows something) and a student (who lacks learning). Yet the person (read: adult woman) with power in these cases is expected to use it to serve, care for, nurture, advocate, or otherwise work on behalf of the vulnerable party. A hierarchy of power, it seems, may not always mean that a relationship is one of domination.

We need to switch to “process thinking” to understand how this can be.

Continued in Part IV.

One thought on “Nonduality Part III: Relationships in Entity Thinking”